-

- Chemaxon Assay

- ChemCurator

- Chemicalize

- ChemLocator

- cHemTS

- Compliance Checker

- Compound Registration

- Administration Guide

- User guide

- Overview

- Compound Registration Introduction

- Compound Registration Abbreviations

- Definitions of Terms

- Quick Start Guide

- Login

- Dashboard page

- Autoregistration

- Bulk Upload

- Advanced Registration

- Search

- User Profile

- Browse page

- Appendix A. Calculations

- Appendix B. Markush Structures

- Multi-Component compounds

- Restricted compounds

- Configuration guide

- Developer guide

- History of Changes

- FAQ

- Design Hub

- History of changes

- Install guide

- Plugin Catalogue

- Developer guide - REST API

- Developer guide - Plugins

- Developer guide - resolver plugins

- Developer guide - real time plugins

- Developer guide - real time plugin templates

- Developer guide - export plugins

- Developer guide - storage plugins

- Developer guide - import plugins

- Developer guide - registry plugins

- Developer guide - theme customization

- Instant JChem

- Instant Jchem User Guide

- Getting Started

- IJC Projects

- IJC Schemas

- Viewing and Managing Data

- Lists and Queries

- Collaboration

- Import and Export

- Editing Databases

- Relational Data

- Chemical Calculations and Predictions

- Chemistry Functions

- Security

- Scripting

- Updating Instant JChem

- Tips and Tricks

- Instant JChem Tutorials

- Building a relational form from scratch

- Building more complex relational data models

- Defining a security policy

- Filtering items using roles

- Lists and Queries management

- Query building tutorial

- Reaction enumeration analysis and visualization

- SD file import basic visualization and overlap analysis

- Using Import map and merge

- Using Standardizer to your advantage

- Pivoting tutorial

- Handling Remote Data with Web Service Entity

- Exploring Canvas Widget in Instant JChem

- Instant JChem Administrator Guide

- Admin Tool

- IJC Deployment Guide

- Supported databases

- JChem Cartridge

- Choral Cartridge

- Using Oracle Text in Instant JChem

- JChem Postgres Cartridge in IJC

- Deployment via Java Web Start

- Startup Options

- Shared project configuration

- Accessing data with URLs

- Instant JChem Meta Data Tables

- Test to Production Metadata Migrator

- Filtering Items

- Deploying the IJC OData extension into Spotfire

- Reporting a Problem

- Manual Instant JChem schema admin functions

- SQL Scripts for Manual Schema Upgrade

- Database Row Level Security

- JccWithIJC

- Instant JChem Developer Guide

- Working With IJC Architecture

- IJC API

- Groovy Scripting

- Good Practices

- Schema and DataTree Scripts

- Simple SDF Exporter

- Relational SDF Exporter

- CDX File Importer

- Data Merger or Inserter from an SDF file

- Markush DCR Structures Exporter

- Select Representative Member of Clusters

- Table Standardizer

- Populate a Table with Microspecies

- Create a Diverse Subset

- Pearson Linear Correlation Co-efficient Calculator

- PDF Trawler

- Simple Substructure Search

- Intersecting Sets

- Find Entries with Duplicated Field Value

- Importing Multiple SDF Files

- Calling External Tools

- Create Relational Data Tree

- Forms Model Scripts

- Button Scripts

- Execute Permanent Query

- Patent Fetcher Button

- Batch Searching Button

- Import or Export a Saved Query SDF Button

- Back and Next Buttons

- Add Annotations Button

- Simple Structure Checker Button

- Advanced Structure Checker Button

- Calculate MolWeight and generate SMILES

- Get Current User

- Simple ChemicalTerms evaluator

- Edit Molecule Button

- TanimotoMultiple

- Execute Permanent Query Based On Its Name

- Open existing view in the same dataTree

- Export selection to file

- Generate random resultset from actual resultset

- Form Scripts

- Groovy Scriptlets

- Buttons vs Scripts

- Creating New Entities

- Creating New Fields

- Reading Molecules From a File

- Insert or Update a Row

- Evaluator

- Create or Find a Relationship

- Adding an Edge to a Data Tree

- Exporting Data to a File

- Connect to an External Database

- Create a New Chemical Terms Field

- Create a New Dynamic URL Field

- Create a New Static URL Field

- Java Plugins

- IJC Plugin Quick Start

- IJC Hello World Plugin

- IJC Plugin tutorial - MyAddField plugin

- IJC Plugin tutorial - MyMathCalc plugin

- IJC Plugin tutorial - Renderer Example

- IJC Plugin tutorial - MySCServer webapp

- IJC Plugin tutorial - MySCClient plugin

- IJC Plugin tutorial - Canvas widget

- Java Plugins and Java Web Start

- Instant JChem FAQ

- Instant JChem Installation and Upgrade

- Instant JChem Licensing

- IJC Getting Help and Support

- Instant JChem System Requirements

- Instant JChem History of Changes

- Instant Jchem User Guide

- Markush Editor

- Marvin Desktop Suite

- MarvinSketch

- User Guide

- Getting Started

- Graphical User Interface

- Working in MarvinSketch

- Structure Display Options

- Basic Editing

- Drawing Simple Structures

- Drawing More Complex Structures

- Drawing Reactions

- Using Integrated Calculations

- Graphical Objects

- Import and Export Options

- Multipage Documents

- Printing

- Chemical Features

- Marvin OLE User Guide

- Appendix

- Tutorials

- Application Options

- Developer Guide

- User Guide

- MarvinView

- Administration guide

- Marvin Desktop Suite - History of Changes

- MarvinSketch

- Plexus Connect

- Plexus Connect - Quick Start Guide

- Plexus Connect - User Guide

- Plexus Connect - Log in

- Plexus Connect - Dashboard

- Plexus Connect - Exporting Your Data

- Plexus Connect - Export Templates

- Plexus Connect - Browsing in Your Data Set

- Plexus Connect - Selecting Data

- Plexus Connect - Searching in Your Database

- Plexus Connect - Saved Queries

- Plexus Connect - List Management

- Plexus Connect - Sorting Data

- Plexus Connect - Sharing Data with Other Users

- Plexus Connect - Charts View

- Plexus Connect - R-group Decomposition

- Plexus Connect - Administrator Guide

- Plexus Connect - Authentication

- Plexus Connect - Sharing Schema Items Among Users

- Plexus Connect - Business Flags

- Plexus Connect - Row-level Security

- Plexus Connect - Shared data sources

- Plexus Connect - Plexus storage

- Plexus Connect - Configuration Files

- Plexus Connect - Simple table

- Plexus Connect - Getting the Plexus Backend and Frontend Log Files

- Plexus Connect - Form Editor

- Plexus Connect - Scripting

- Plexus Connect - API keys

- Plexus Connect - Deploying Spotfire Middle Tier solution

- Plexus Connect - Installation and System Requirements

- Plexus Connect - Licensing

- Plexus Connect - Getting Help and Support

- Plexus Connect - FAQ

- Plexus Connect - Privacy Policy

- Plexus Connect - Demo Site

- Plexus Connect - History of Changes

- Plexus Connect - Schema Refresh Without Restart

- Plexus Connect - Video Tutorials

-

- AutoMapper

- Calculator Plugins

- Introduction to Calculator Plugins

- Calculator Plugins User's Guide

- Calculator Plugins Developer's Guide

- Calculators in Playground

- Background materials

- Calculation of partial charge distribution

- Generate3D

- Isoelectric point (pI) calculation

- LogP and logD calculations

- NMR model prediction

- pKa calculation

- Red and blue representation of pKa values

- Tautomerization and tautomers

- Validation results

- Tautomerization and tautomer models of Chemaxon

- Theory of aqueous solubility prediction

- The tautomerization models behind the JChem tautomer search

- Calculators performance reports

- Calculator Plugins Licensing

- Calculator Plugins FAQ

- Calculator Plugins Getting Help and Support

- Calculator Plugins History of Changes

- Calculator Plugins System Requirements

- Chemaxon .NET API

- Chemaxon Python API

- Chemaxon Cloud

- User Guide

- Developer Guide

- Glossary

- Document to Structure

- JChem Base

- Administration Guide

- Developer Guide

- User Guide

- Query Guide

- Search types

- Similarity search

- Query features

- Stereochemistry

- Special search types

- Search options

- Atomproperty specific search options

- Attached data specific search options

- Bond specific search options

- Chemical Terms specific search options

- Database specific search options

- General search options

- Hitdisplay specific search options

- Markush structure specific search options

- Performance specific search options

- Polymer specific search options

- Query feature specific search options

- Reaction specific search options

- Resultset specific search options

- Similarity specific search options

- Stereo specific search options

- Tautomer specific search options

- Tautomer search - Vague bond search - sp-Hybridization

- Standardization

- Hit display-coloring

- Appendix

- Matching Query - Target Examples

- jcsearch Command Line Tool

- jcunique Command Line Tool

- Homology Groups in Markush Structures

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) search

- Query Guide

- FAQ

- History of Changes

- Getting Help and Support

- JChem Choral

- JChem Microservices

- Introduction

- Administration Guide

- Developer Guide

- Calculations Web Services

- DB Web Services

- IO Web Services

- Markush Web Services

- Reactor Web Services

- Structure Checker Web Services

- Structure Manipulation

- Task Manager

- Second Generation Search Engine

- JChem Microservices FAQ and Known Issues

- JChem Microservices History of Changes

- JChem Oracle Cartridge

- JChem PostgreSQL Cartridge

- JKlustor

- Markush Tools

- Marvin JS

- User Guide

- Getting Started

- Editor Overview

- Editor Canvas

- Dialogs

- Toolbars

- Context Menus

- Drawing and Editing Options

- Feature Overview Pages

- Keyboard Shortcuts

- Developer Resources

- History of Changes

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Video Tutorials

- Comparison of Marvin JS and MarvinSketch Feature Sets

- User Guide

- Marvin

- Molconvert

- Name to Structure

- Reactor

- Reactor User's Guide

- Introduction to Reactor

- Reactor Getting Started

- Reactor Concepts

- Reactor Examples

- Working with Reactor

- Specifying Reactions

- Specifying Reactants

- Reaction Mapping

- Reaction Rules

- Reactant Combinations

- Running Reactor

- Reactor Interfaces

- Reactor Application

- Reactor Command-line Application

- Reactor in Instant JChem

- Reactor in JChem for Excel

- Reactor in KNIME

- Reactor in Pipeline Pilot

- API, Web Services

- Glossary

- Reactor FAQ

- Reactor Licensing

- Reactor Getting Help and Support

- Reactor History of Changes

- Reactor Configuration Files

- Reactor User's Guide

- Screen

- Standardizer

- Standardizer User's Guide

- Standardizer Introduction

- Standardizer Getting Started

- Standardizer Concepts

- Working with Standardizer

- Standardizer Actions

- Add Explicit Hydrogens

- Alias to Atom

- Alias to Group

- Aromatize

- Clean 2D

- Clean 3D

- Clear Isotopes

- Clear Stereo

- Contract S-groups

- Convert Double Bonds

- Convert Pi-metal Bonds

- Convert to Enhanced Stereo

- Create Group

- Dearomatize

- Disconnect Metal Atoms

- Expand S-groups

- Expand Stoichiometry

- Map

- Map Reaction

- Mesomerize

- Neutralize

- Rearrange Reaction

- Remove Absolute Stereo

- Remove Atom Values

- Remove Attached Data

- Remove Explicit Hydrogens

- Remove Fragment

- Remove R-group Definitions

- Remove Stereo-Care Box

- Replace Atoms

- Set Absolute Stereo

- Set Hydrogen Isotope Symbol

- Strip Salts

- Tautomerize

- Transform

- Ungroup S-groups

- Unmap

- Wedge Clean

- Remove

- Standardizer Transform

- Custom Standardizer Actions

- Remove Solvents

- Creating a Configuration Standardizer

- Interfaces Standardizer

- Standardizer File Formats

- Standardizer Actions

- Standardizer Developer's Guide

- Standardizer Installation and System Requirements

- Standardizer Licensing

- Standardizer Getting Help and Support

- Standardizer History of Changes

- Standardizer User's Guide

- Structure Checker

- Structure Checker User's Guide

- Introduction

- Structure Checker Getting Started

- Structure Checker Concepts

- Working with Structure Checker

- Checker List

- Abbreviated Group

- Absent Chiral Flag

- Absolute Stereo Configuration

- Alias

- Aromaticity Error

- Atom Map

- Atom Query Property

- Atom Value

- Atropisomer (deprecated)

- Attached Data

- Bond Angle

- Bond Length

- Bond Topology

- Brackets

- Chiral Flag

- Chiral Flag Error

- Circular R-group Reference

- Coordination System Error

- Covalent Counterion

- Crossed Double Bond

- Double Bond Stereo Error

- Empty Structure

- Explicit Hydrogen

- Explicit Lone Pairs

- EZ Double Bond

- Incorrect Tetrahedral Stereo

- Isotope

- Metallocene Error

- Missing Atom Map

- Missing R-group

- Molecule Charge

- Multicenter

- Multicomponent

- Multiple Stereocenter

- Non-standard Wedge Scheme

- Non-stereo Wedge Bond

- OCR Error

- Overlapping Atoms

- Overlapping Bonds

- Pseudo Atom

- Query Atom

- Query Bond

- Racemate

- Radical

- Rare Element

- Reacting Center Bond Mark

- Reaction Map Error

- Relative Stereo

- Ring Strain Error

- R-atom

- R-group Attachment Error

- R-group Bridge Error

- Solvent

- Star Atom

- Stereo-Care Box

- Stereo Inversion Retention Mark

- Straight Double Bond

- Substructure

- Three Dimension 3D

- Unbalanced Reaction

- Unused R-group

- Valence Error

- Valence Property

- Wiggly Bond

- Wiggly Double Bond

- R-group Reference Error (discontinued)

- Wedge Error (discontinued)

- Creating a Configuration

- Custom Checkers and Fixers

- Interfaces of Structure Checker

- Checker List

- Structure Checker Developer's Guide

- Structure Checker Installation and System Requirements

- Structure Checker Licensing

- Structure Checker Getting Help and Support

- Structure Checker History of Changes

- Structure Checker User's Guide

- Structure to Name

-

- JChem for Office

- Administration Guide

- User Guide

- JChem for Excel User's Guide

- JChem for Excel Ribbon

- Working with Structures in Excel

- Add a Structure to a Cell

- Edit a Structure in a Cell

- Edit Structures in the Task Pane

- Resize Structures

- Structures in Merged Cells

- Show and Hide Structures

- Show and Hide Structures and Structure IDs

- Insert Single Structures

- Open Structure Files

- Delete Structures from a Selected Range

- Save Single Structure to a File

- Print Structures

- Copy and Paste with JChem for Excel

- Convert from Structures

- Convert to Structures

- Convert ISIS, ChemDraw, Accord, and Insight for Excel Files to JChem for Excel Files

- Calculations with Third-Party Services

- Specify External Image and Name Services

- Importing from Databases in JChem for Excel

- Manage Connections

- Add an Oracle Connection in JChem for Excel

- Add a MySQL Connection in JChem for Excel

- Add an MSSQL Connection in JChem for Excel

- Add a PostgreSQL Connection in JChem for Excel

- Add a JChem Web Services Connection in JChem for Excel

- Favorite Entities in JChem for Excel

- Edit and Delete Connections in JChem for Excel

- Import from Database in JChem for Excel

- Import from IJC Database in JChem for Excel

- Import from Database by IDs

- Manage Connections

- Resolve ID

- Import from File

- Export to File

- Share Excel Files

- R-group Decomposition in JChem for Excel

- SAR Table Generation

- Structure Filter

- Options in JChem for Excel

- General Options in JChem for Excel

- Database Connection Options

- Formatting Options

- Licensing Options in JChem for Excel

- File Import Options in JChem for Excel

- IJC Import Options in JChem for Excel

- File Export Options in JChem for Excel

- Printing Options in JChem for Excel

- Structure Sheet Options

- Image Conversion Options

- Structure Display Options in JChem for Excel

- Structure Editor Options in JChem for Excel

- Event Handling Options in JChem for Excel

- Actions

- Functions in JChem for Excel

- Setting ACS 1996 style in JChem for Excel

- Custom Chemical Functions in JChem for Excel

- Use Custom Chemical Functions

- Functions Reference

- Normal

- Charge in JChem for Excel

- Chemical Terms in JChem for Excel

- Dissimilarity

- Drug Discovery Filtering in JChem for Excel

- Elemental Analysis in JChem for Excel

- Geometry in JChem for Excel

- Hydrogen Bond Donor-Acceptor in JChem for Excel

- Isomers in JChem for Excel

- Naming

- Protonation and Partitioning in JChem for Excel

- Solubility

- Tautomers in JChem for Excel

- Topology Analysis in JChem for Excel

- Structure in JChem for Excel

- Image

- Normal

- User Interface Customization in JChem for Excel

- Checking DirectX Information

- JChem for Office User's Guide

- JChem Ribbon

- Working with Structures

- Importing from Databases in JChem for Office

- Manage Connections in JChem for Office

- Add an Oracle Connection in JChem for Office

- Add a MySQL Connection in JChem for Office

- Add an MSSQL Connection in JChem for Office

- Add a PostgreSQL Connection in JChem for Office

- Add a JChem Web Services Connection in JChem for Office

- Favorite Entities in JChem for Office

- Edit and Delete Connections in JChem for Office

- Import from Database in JChem for Office

- Import from IJC Database

- Manage Connections in JChem for Office

- Import from File in Jchem for Office

- Options in JChem for Office

- Properties in JChem for Office

- Switching JChem for Office to Lite Mode

- User Interface Customization in JChem for Office

- JChem for Office Lite User's Guide

- JChem for Office Known Issues

- Troubleshooting

- Troubleshooting - JChem for Office

- Structures are not displayed in Excel cell

- JChem for Office Tutorial Videos

- Enable JChemExcel.Functions add-in after it gets disabled

- Structure rendering issues when moving the Excel window between different screens

- How to collect event logs

- Information to be sent for bug investigation

- Logfiles to be sent for bug investigation

- Diagnostic Tool

- JChem for Excel User's Guide

- History of Changes

- KNIME Nodes

- JChem for Office

-

- Chemaxon Configuration Folder

- Chemical Fingerprints

- Chemical Terms

- File Formats

- Basic export options

- Compression and Encoding

- Document formats

- Graphics Formats

- Molecule file conversion with Molconvert

- Molecule Formats

- CML

- MDL MOL files

- Daylight SMILES related formats

- Chemaxon SMILES extensions

- IUPAC InChI, InChIKey, RInChI and RInChIKey

- Name

- Sequences - peptide, DNA, RNA

- FASTA file format

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) file format

- Tripos SYBYL MOL and MOL2 formats

- XYZ format

- Gaussian related file formats

- Markush DARC format - VMN

- CSV

- Input and Output System

- License Management

- Long-Term Support (LTS)

- Notice about CAS Registry Numbers®

- Public Repository

- Scientific Background

- Structure Representation

- Structure Representation - Class Representation

- Aromaticity

- Implicit, Explicit and Query Hydrogens

- Assigning stereochemistry descriptors

- Cleaning options

- Deprecated and Removed Methods

- Relative configuration of tetrahedral stereo centers

- Iterator Factory

- Atom and bond-set handling

- Graphic object handling

- Supported Java Versions

- Used Libraries

-

- BioEddie

- Biomolecule Toolkit

- Document to Database

- Fragmenter

- JChem Neo4j Cartridge

- JChem Web Services Classic

- Markush Overlap

- MarvinSpace

- MarvinSpace User's Guide

- MarvinSpace Developer's Guide

- MarvinSpace History of Changes

- Metabolizer

- Pipeline Pilot Components

- Trainer Engine

Calculation of partial charge distribution

This material describes the concepts behind our partial charge distribution calculation:

Introduction

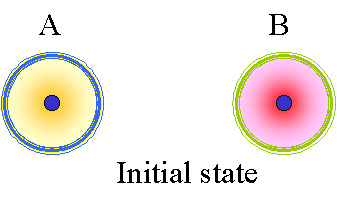

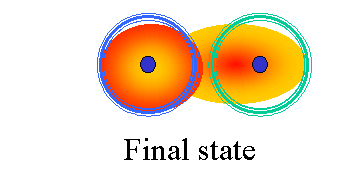

Chemical bonds between atoms within a molecule consist of one or more electron pairs distributed among the connected atoms. Bonding electrons are not equally distributed among the atoms that have different electronegativity. Forming a chemical bond can be formally described with the following three steps:

-

Initial state

In this case we can speak about partial charge of atoms. We will give the definition of partial charge intuitively rather than exactly. A simple definition of partial charge starts from a basic two-atom model in which atoms A and B have different electron structures. In the figure below, the "boundary" of the valence shell is denoted with blue and green solid lines. This boundary is chosen to create a fixed control volume with a definite probability (near to 100%) of finding all electrons belonging to the atom on the inside.

Fig. 1 Initial state of two different atoms

Fig. 1 Initial state of two different atoms -

Intermediate state In the intermediate state the nuclear distance of A and B decreases. As they draw closer to each other, each of their electron clouds is polarized to a different degree. Although the electrons of both A and B have partially moved outside of the control volume, this effect is greater in atom B being the more polarizable atom. The more polarizable an atom is, the more electrons will flow out of its control volume so that the atom will become more positive relative to its initial state.

Fig. 2 Intermediate state of two different atoms

Fig. 2 Intermediate state of two different atoms -

Final state In the final state the two atoms reach the equilibrium nuclear distance and the two electron clouds overlap. Using the control volumes and electron clouds in the figure, atom B becomes more positively charged and atom A becomes more negatively charged relative to their initial states. In this way, partial charge of an atom in the molecule is measured as a charge flow out of or into the atom's control volume.

Fig. 3 Final state of the two different atoms

Fig. 3 Final state of the two different atoms

Concept of orbital electronegativity

Partial charge distribution of the molecule is governed by the orbital electronegativity of the atoms contained in the molecule. The definition of orbital electronegativity of atoms in molecules was first given by Mulliken by the following equation:

χν = 0.5(Iν+Eν)*

where:

-

χν is the orbital electronegativity of the atom.

-

I ν is the ionization potential of the atom.

-

E ν is the electron affinity of the atom.

The orbital electronegativity of the molecule depends on the hybrid state and partial charge of the atom, see references of Mcweenyand Dewar. Electronegativity is a quadratic function of partial charge given by the following equation:

χν = a+bq+cq 2

where:

-

q is the partial charge on the atom;

-

a , b , and c are coefficients determined from I ν and E ν.

Orbital electronegativity and subsequently partial charge distribution of any molecule is calculated iteratively.

Examples

Here are some examples for partial charge calculation.

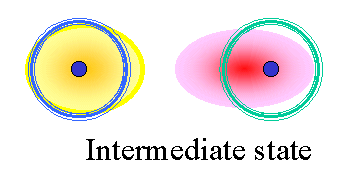

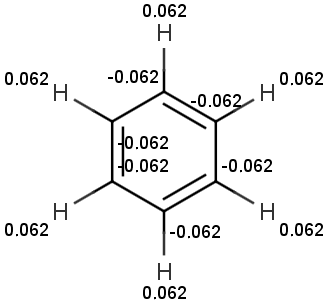

Example #1

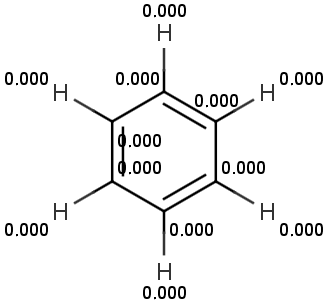

In benzene every carbon atom has the same electronegativity. This is why the partial charge distribution is identical among the carbon atoms. The total partial charge of the hydrogen atoms has the same magnitude with opposite sign. The π partial charge is zero for all atoms in the benzene. In our model, the total charge is composed of two independent components - the π and σ partial charges, which are determined by the π and σ bonds, respectively.

Total charge and π charge distribution of benzene can be seen below.

Fig. 1 Total charge and π charge distribution of the benzene molecule

Example #2

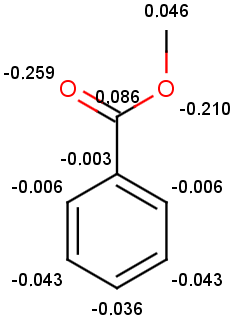

In ring substituted benzene, the partial charge distribution helps to predict the reactivity of the carbon atoms that are members of the ring. If the substitute is electron-donating, the partial charge increases in the ortho and para positions of the aromatic ring. If the substitute is electron-withdrawing, partial charge decreases in the ortho and para positions.

The figure below shows that the total partial charge reaches a maximum at the meta position relative to the other aromatic atoms due to the electron-withdrawing effect of methoxycarbonyl group.

Fig. 2 Partial charge distribution of ring substituted benzene

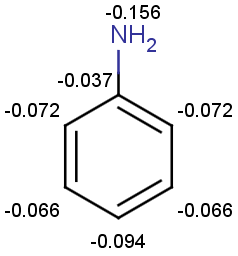

Since the amine group is electron releasing, the total partial charge reaches a maximum (relative to the other aromatic positions) at ortho and para positions.

Fig. 3 Partial charge distribution of benzamine

Example #3

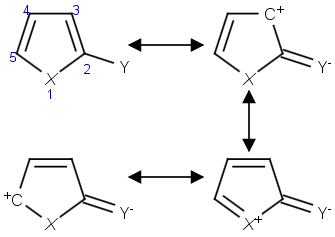

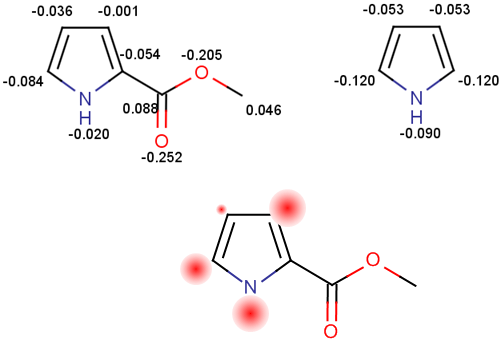

The effects of substitution in five membered aromatic rings can also be described with resonance structures.

Fig. 4 Resonance structures describing the substitution in five-membered rings

Let Y stand for a methoxycarbonyl group and let X represent nitrogen. The calculated partial charge distributions of methyl 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate and pyrrole are given below. The size of each red spot represents the accumulated excess positive charge. From resonance structures we would expect positive partial charge to increase at positions 1, 3 and 5. This expected distribution agrees with the calculated ones.

Fig. 5 Partial charge distributions of methyl 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate and pyrrole

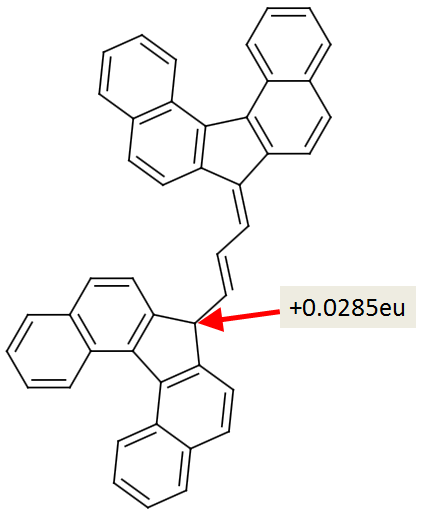

Example #4

Hydrocarbons usually have weak acidic character. Carbon atoms have different partial charges and ability to delocalize excess negative charge after the loss of a proton. The more positive partial charge accumulated on the carbon atom, the more acidic its character.

From partial charge calculations, we find that all the carbon atoms have negative partial charge except for the one indicated by a red arrow. The most acidic carbon atom at the tip of red arrow has partial charge of +0.0285 electron unit. This result agrees with the published result, see Stewart et al.

Fig. 6 Weak acidic carbon atoms in hydrocarbon molecule

References

-

Mulliken, R.S., J. Chem. Phys. , 1934 , 2 , 782; doi

-

McWeeny, R., Coulson's Valence , Oxford University Press, 1979

-

Dewar, M.J.S., The Molecular Orbital Theory of Organic Chemistry , McGraw-Hill, and Inc., 1969

-

Gasteiger, J.; Marsili, M., Tetrahedron , 1980 , 36 , 3219; doi

-

Stewart, R., The Proton: Applications to Organic Chemistry , Academic Press, Inc., 1985 , 72